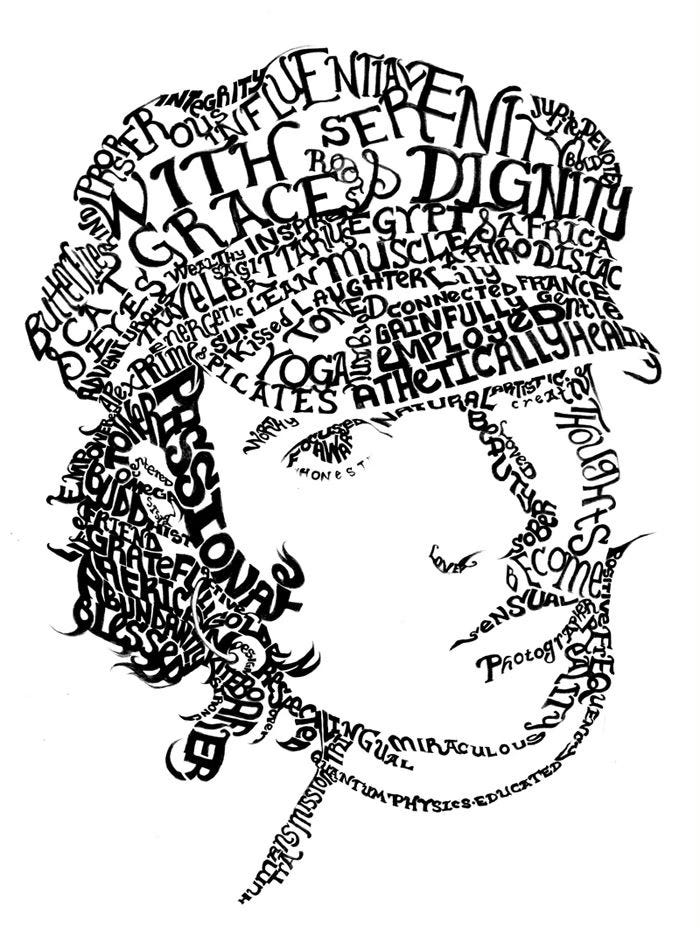

Portrait of an Artist in Words

Inspired by Geoff Dyer's collection of Vignettes "But Beautiful."

He was a cliff-jumping backcountry skier and life was the untouched powder. He liked to shoot, go all in, cast a fishing line as far out as he could, throw the dice, play Russian roulette. He didn’t pursue experiences if he could control them, know which way they would turn out. He had inviolable faith in surrendering to chance, for him both glimmering seductress and truest of loves. He felt a kind of poignancy and tenderness for chance when he couldn’t afford to take it; like a laborer obliged to leave home for opportunity he knew that, despite having to bid her adieu time and again, he would always come back no matter how long it took.

He could never have enough of playing the odds. As soon as he felt himself settling down, like stirred-up mud clouds slowly sinking to the bottom of a river, his spirit would rile him up again like a startled fish. He knew when he was letting himself slide, cheating, going back to the old tried-and-true approaches he had used before; it was an alarm bell telling him that it was time to cut loose. For him, the path was as steep as infinity: no compromises, and no diluting his essence. Yet, the amber light of his eyes was still soft as down feathers.

He needed to feel risk, the rawness and authenticity of it, because, in the end, what point could there be in playing it safe? He felt the same way about life that a free-solo climber feels about ascending sheer faces of rock; what gave each elegant motion meaning was that he could slip off and die at any moment. He’d ride his bike in narrow lanes next to hostile traffic, on the edge of clearance with parked-car doors that threatened to open at any moment. It woke him up, focused him, made him feel alive. He’d hang around people on the edge because they reflected back to him where he wanted to be. One time, a guy he made friends with in the park lost his grip, pulled a gun on him on the street as a joke. Gazing down the barrel, he thought of how beautiful the green dot looked on the sight.

He injected untamed life into staid parties. But rather than a megaphone that cuts above the noise, he was more like a bushfire in the dead of night that dazzled the eyes of ancient peoples. As soon as they met him, even the dull and distracted recognized that he knew something about life that they didn’t. He never needed to overexert himself, push hard to make a mark. His power was one of suction, letting his aura do all the work of drawing people across a gradient of spiritual osmosis. The insights he added to conversation were enigmatic but pierced below the surface as suddenly and sharply as a needle into skin, or an olympic diver whooshing into crystal waters from a great height.

He exuded sincerity and love but, like a wizened zen priest, held onto a mischief-making streak; as far as he was concerned, mooning the smug, or simply scandalizing them verbally, just might nudge them a little closer to enlightenment. From time to time he liked to test his ability to hypnotize, not to take advantage of anyone but just to feel the thrill of a captive audience. He’d tell wild tales, crack jokes, enchant and beguile women at the table with his mystique and wit. Coming from a small town in America’s far west, it was his way of finding what communion he could with upper-crust cosmopolitan girls who thought they had heard it all.

He liked to slip in and out of the streams of strangers’ trances, camouflaging himself into their world and catching them right at the peak of their energetic arcs. In those moments, people felt like they had always known him, that his intrusions didn’t trip any wires. One time, a guy was dapping his friends and family up in the subway, telling them they’d catch each other soon. Just as the convivialities were coming to a close and the shutting of the doors loomed, he’d get in on the action:

“Goodnight man”

“A’ight man, goodnight.”

Somehow, he was just light and transitory enough to fit in, floating along the edges of groups like a pin held up by the delicate skin of surface tension on water. He knew that the fragile equilibrium protecting him from aggression or contempt could be broken at any time, but he wouldn’t have it any other way.

He was a pop quiz life threw at you to see where you really are, not what you say— a look in the mirror, no photoshop. He liked to open people up right away, like a surgeon. The heart of the matter, the good stuff, the dirty details: those were too good to let lie fallow in the fields of social convention. He couldn’t help himself, sometimes going too far too quickly before they were ready to be laid bare. Realizing how closed off some people are, he’d switch the surgical lights off, sew a few stitches, and pivot to the next thing that didn’t turn him off.

Any time he found himself in the company of strangers, he’d ask more questions than anyone, using them to orient himself to the milieu, to trace the shape of each person’s interior the way a bat uses echolocation to map the night sky. To those who carried heavy weights, he was the confessional priest they didn’t know they needed. To those who preferred to guard themselves, he was the paparazzi at the door. Either way, he knew more about you than you knew about yourself. Now that’s some cold water on your face in the morning.

He knew how to leave a reverberating impression, but also how to disappear without a trace, delicately as a single blood-crimson leaf falling from a tree at the height of autumn. Even when it was someone’s job to carry him (a waiter’s or doctor’s, perhaps), he wanted to be as light in their presence as a daydream would be in their minds. He didn’t like to take space, he said — no, he liked to make space. Liked to make time, too, delighting in unmeasured chunks of reverie like a child laughing, not a care in the world, tearing off pieces of bread with his hands. Time waits for no man, but his sprawling, meandering nonchalance made it seem like he made time wait for him.

The great outdoors and anything in motion was his home more than anything at rest. He was at his best in transit, improvising like a jazz musician over the chord changes life threw at him, always getting what he needed on the fly; he knew he could almost always count on the kindness of people passing through his world to help him disentangle the knots he’d unconsciously pulled tight behind him as he worked. If he could have it his way, he’d carry his life in a suitcase, letting go of creature comforts and making the road his studio. And besides, he liked building things on quicksand — instability was an indispensable part of the thrill.

He resisted forcing himself into social shapes, avoided putting on a pretty face to appease anyone who might rush him, demand something of him. He had what an intellectual who travelled to remote islands in Papua New Guinea saw in the native people: something different in their eyes, something far more at home, centered, embodied, than those swaddled in the cradle of modernity. No, he didn’t want any part of his life cubicled, outsourced, cordoned off from the whole. It would be foolish, he thought, to sell his birthright for things as overrated as comfort. If modern life was an assembly line, he wanted to be the lone craftsman on strike who would do it all from start to finish. After all, how you do anything is how you do everything, he said.